A Company C Boy Talks About The War

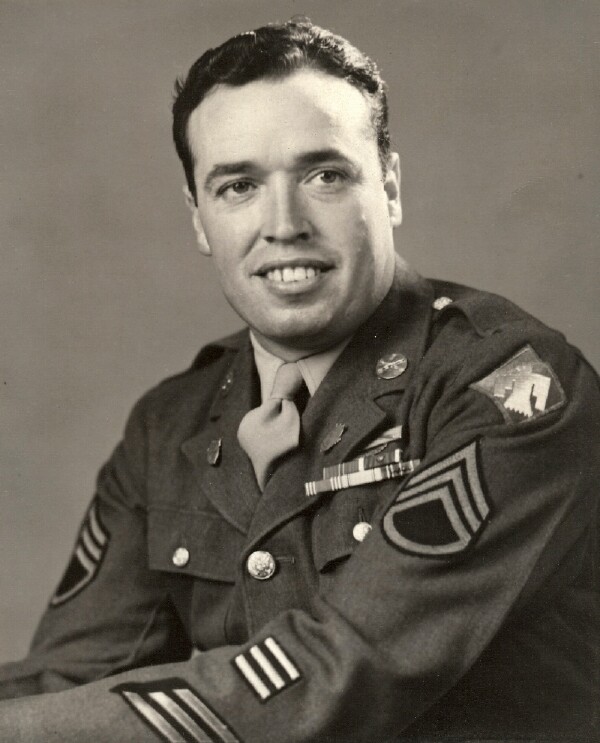

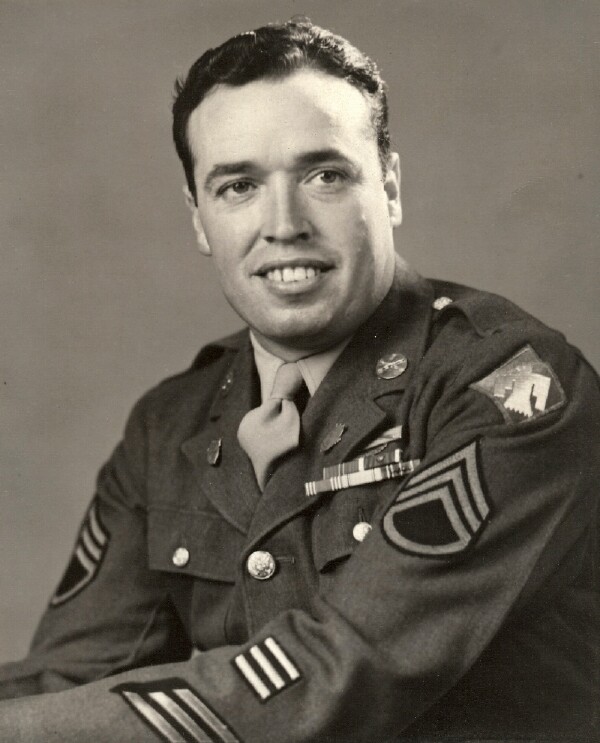

Almost within sight of German soil, when he was returned to this country, Staff Sergeant William A. Gehring, now in Delta on furlough, can speak of fanatical Nazi homeland defense with authority.

As a platoon sergeant in a rifle company of the 45th Infantry Division, the “Thunderbird Division”, Sergeant Gehring fought the Germans in Sicily, Italy and southern France. His experience is that the closer home the

Germans get, the harder they fight.

“I was last in action about 50 miles from the German border, near the Belfort Gap.” Sergeant Gehring related, “and the going was getting rougher all the time. In Sicily and Italy, and even when we first landed in France, the Jerries would fight awhile and then run to another spot. But now they stay and die.”

The veteran of 17 months of infantry action saw his first combat at Gela during the invasion of Sicily.

Following the Sicilian campaign he went to Italy, landing at Salerno a few days after D-Day, just when the Germans were trying to push the Americans off the beach.

After fighting at both Casino and Anzio and marching beyond Rome after the breakthrough, he next landed in France at St. Maxime.

An Infantry platoon sergeant is second in command of his platoon and must be everywhere to check on the dispositions of his men and keep control so that the actions of the individual Doughboys may be

coordinated. Often he must expose himself to enemy fire in his efforts to see that his men are effectively deployed. Twice the law of averages caught up with Sergeant Gehring.

“We learned a lot of things the hard way over there.” The platoon sergeant explained. “And we learned about German mines that way.

I was first wounded in Sicily, near San Stefano, when our company came up against a minefield.

“The second time I was wounded was near Buenevento, Italy. We were attacking a small hill outside of a small town and the Germans were spraying us with artillery fire. A shell fragment struck me.

“There may have been spots where the fighting was hotter for awhile.” He declared, “but there has never been anything like Anzio for continued hell. There wasn’t a place on the beachhead where you could relax and feel safe because it was all under artillery fire. When Doughboys speak of “the beachhead,” they mean Anzio. Not even Salerno can claim that distinction.”

Sergeant Gehring considers himself lucky in one respect. “I got out of France just as it started to rain,” he smiled. “That’s when ground troops have it rough, in the rain and mud. But it hasn’t stopped the Infantry yet and never will.”

Proof that Infantry life is hard lies in Sergeant Gehring’s revelation that of a full Infantry company that left the states 17 months ago, only 25 are still in combat.

“Some are dead, some are prisoners, others are wounded, and still others have been reclassified for rear area work,” he explained.

“The Infantry is tough, all right, but there’s a lot of variety to it – a number of different weapons to master, different tactics to apply in various situations, and lots of humor, some funny and some not so funny.”

Sergeant Gehring’s battalion holds a distinguished unit citation for the “Battle of the Caves” at Anzio, where American troops, surrounded by Germans, fought until they were rescued.

He also has been awarded the Combat Infantryman Badge for exemplary conduct in action against the enemy, and holds the Purple Heart with Oak Leaf Cluster for two wounds, the Good Conduct Medal, Pre-Pearl Harbor ribbon and campaign ribbon with stars for Sicily, Italy and France.

The Infantryman is spending his furlough with his wife, Mrs. Maggie Gehring, of 406 West Fourth Street, and his mother, Mrs. J. Quint, of Montrose, Colorado.