Russel Weiskircher

|

|

It's always a pleasure and an honor to receive an email from a WWII vet, especially

a brigadier general with 45 years of service to his country. His medals include

the Legion of Merit, the Silver Star, the Bronze Star and three Purple Hearts.

He also served as an instructor with the ROTC and the Army War College. Russel,

PhD, STD, B. Gen AUS-Retired, is vice-chairman of the Georgia Holocaust Commission.

He decided to write to me after being introduced to my site by Diane Kessler, contributor of the 70th Division's website.

I'm thrilled that he is willing to share his memoirs from his experiences with

the 45th Infantry Division and his continued service beyond 1945.

I will be 80 years of age on Jan 5,05 and I have been retired and residing here in North George since 1992. More later, happy new year. Russ Weiskircher, BG AUS Retired.

They tell me I first saw the light of day in 1925, arriving at a rural farmhouse in Wildcat Hollow near Elizabeth, a sleepy little burg in Southwestern Pennsylvania, ten miles from McKeesport, thirty miles from Pittsburgh. My parents were honest, God-fearing farm and mill folks. I was the product of devoted family, dedicated teachers and supportive community. From this background, immediately after Pearl Harbor, stems my military tale.

|

My older brother, ten years my senior, was off to the war and spent most of WWII in the Pacific theater working with radios and artillery communications. I wanted to go to college but realized that service came first. I tried to schedule it immediate after graduation from high school but fate delayed me while I dueled with the induction center doctors who kept rejecting me due to some kidney infection, which my old country doctor labeled hereditary, transient and meaningless. I was turned down four times but on the fifth try I slipped a janitor in the Old Federal Building a quick fin to produce the necessary urine specimen. It worked, and I qualified to join the fighting ranks.

|

|

300

man barraks at Fort George Meade, Maryland

|

My early introduction to the military included my first long time absence from home, my first long distance train ride and my first homesickness. Orientation was at Fort Meade, Maryland where I spent about ten days getting inoculations, orientations, uniforms and equipment. I was a veritable heap of wrinkled fatigues, khakis, duffel bag, leggings and footwear. Here I got my first taste of army routine, barracks life, discipline and a formal introduction to the power of even a lowly PFC. Here I met the dreaded KP, and sentry duty and extra duty and the certain knowledge that silence was golden and volunteer was an ugly word. Here I formed my first GI friendships, some of which have lasted a lifetime to date. One such instant friend was Charlie Z---------, a young farm lad who hailed from a small town about fifty miles from home. Since we were organized and housed and trained alphabetically, this W and Charlie's Z was constantly together.

Wake up, fall in, and sound off! It was assignment day and despite days of testing and interviewing, the need for cannon fodder overrode any scientific or professional placement. I was to transfer immediately to the Infantry Replacement Training Center (IRTC) at Fort McClellan, Alabama. And so it was off for Alabama with my barracks bag on my knee. We traveled in old day coaches with wooden seats. They added latrine and kitchen cars and off we went from Fort Meade via the B&O right back through Pittsburgh and right past my hometown where I could see my house.

I remember wanting to spare my new khakis the soot and grime from the steam engine, so I changed into fatigues. Wrong! The transport Corporal came into our car, pointed to me and said four more of you get into your fatigues and join this man in the mess car. Because I was in the right uniform at the wrong time or maybe the wrong uniform at the right time, I peeled spuds from Maryland to Pennsylvania to Ohio and south to Atlanta. Along the way we had a collision with a big rig at a rural crossing. The rig was carrying a load of gingerbread mix and the scene was one of ginger dust and spicy smell.

|

|

Post

card from Ft Mc Clellan, Anniston Ala.

|

Life in the IRTC is hardly worth describing. We put in long days; often busy nights, forced marches, and weapons training. We were taught to survive and to fight the infantry war. I struggled, but learned and grew lean and mean and determined to do my bit.

Seventeen long training weeks later,

including Thanksgiving and the loneliest Christmas and New Years days, we graduated

and headed home for a seven-day leave and then to our initial assignment. Before

I leave the basic scene I need to comment upon the miserable but rewarding fifteen-mile,

full-field hikes over Baines Gap. I need also to remember the beautiful and

inspiring Silver Chapel on the main post. I recall some writing for our training

cycle newspaper. I was named the training battalion volunteer reporter. Of course

my training sergeant volunteered me because I could read and write something

remotely akin to English.

|

|

St.

Michael's and All Angels Episcopal Church

|

I remember also my single trip off post and my one and only weekend in Anniston. I recall the generosity and hospitality of the ladies of St. Michael's and All Angels Episcopal Church. They provided bed and shower and breakfast, all for fifty cents; free if you were broke. In Anniston I also encountered the deep, segregated south. This yank interfered when a local citizen attempted to cane a young black lad who committed the sin of treading on the sidewalk in front of a whites only theater. I nearly went to jail when I made the old man stop beating the young black. The military police rescued me. Hauled me back to camp and "wised me up" So end my basic memories.

Charlie and I traveled together to my home where his parents met him. When we went back, his parents asked me to look after him and keep him safe and bring him back. I said I would, and I meant it. This was to be one of the saddest lessons of my short life and my real introduction to the reality of war.

After a too brief leave, it was goodbye to family and the sweet young lady who became the love of my life and my soul mate for life.

With every new adventure, there comes a new language, a nomenclature to remember. Such is the case with the military and I want to list a few key words. Transient, casual, replacement, transport, temporary, rations, troop ship, troop train, troop list, roll call, tent city, clip board, latrine. Alone, these words mean little but put them altogether and if I recall correctly, it spells TRIP. Here are some trip recollections that cover the time span of January and February 1943.

After basic training and after a wonderful but all too brief home leave, it was back to duty and POM. That's army talk for preparation for overseas movement. From home to Fort Meade, Md. was routine. Early one morning, right after roll call I was summoned to the orderly room and given an on the spot promotion to acting corporal. I learned that this was a dubious honor, more like a lot of temporary responsibility and a meaningless title for the duration of my overseas trip. Who picks and promotes is still a mystery to me but I am certain that it is an experience never to be forgotten. With my new stripes on my sleeve and surrounded by many fellow casuals, we went back to Fort Meade where we were matched up, fresh troops for the European front, and shipped out to Camp Patrick Henry near Newport News, Virginia. I had been promoted to PFC after basic and now was selected to be a "salt water" non-com. That is an acting corporal for the transient journey overseas. My first taste of responsibility and leadership and the demands and privileges of rank, even the temporary kind. After they verified our shots and our training record, we were herded aboard the SS General Mann, 15000 troops to move in convoy down the Atlantic Coast to a spot opposite Natal, Brazil and then east towards Dakar, Africa. Charlie and I stayed together along with about 15,000 replacements.

|

|

USS

General W.A. Mann (AP 112)

|

Crowded, smelly. Sweaty, noisy, hot, uncomfortable; those are appropriate adjectives. We were jammed into holds with bunks as many as five high. Seasickness was the order of the day. We showered in salt water; we ate well when we were well enough to want to eat. We have endless abandon ship drills. We went topside for calisthenics daily. We observed strict light discipline at night. We moved at the speed of the slowest tankers that accompanied our convoy. Submarine drills, submarine alerts, sirens in the middle of the night, blackouts. I learned one thing; anything on land, anywhere, is preferable to being cooped up on a crowded ship on the ocean. It took us nine long days via slow convoy to traverse the Atlantic.

My African experience is fleeting and sketchy. Eventually, we arrived at Casablanca and were temporarily housed in huge tent cities. I remember mess tents and pyramidal sleeping quarters and latrines. We had little to do but wait for the system to call our name out over the public address system. That was the signal to report to the troop train!

Hello Forty and Eight boxcars! We had steam engines to pull our cars, on narrow gauge railroad tracks, with old wooden cars designed to carry 40 men or 8 horses that hauled us over the Atlas Mountains. We were about twenty-five troops to each car. Three days in stinking cars that had been used to haul horses, horses that certainly didn't suffer from kidney problems. We missed the animals but not the smells.

We traveled so slowly up the hills and steep grades, often walking along side the cars. We hopped aboard as we headed downhill. We had mechanical brakes attended to by a native who rode on the roof and wore a turban. He appeared to sleep on the level and uphill grades but at the sound of a whistle he sprang into action and manually operated a screw valve control that broke our screeching lurching downhill progress over the Atlas Mountains from Casablanca to Oran.

It took a couple of days. We played cards. Tried to sleep and write mail. We were permitted to say that we were in Africa but we didn't where we were or where we were headed.We passed many small mud and metal huts. Women and kids flocked out with oranges, begging for candy and cigarettes and chewing gum. The kids were dirty, the women a sad lot and the oranges looked diseased with a warty red skin, but we ate the fresh fruit. We ate C rations, cold. The native women and children that ran to greet us begged for the empty ration cans and boxes. They flattened the tins and waterproofed their miserable huts.

After the train-ride, another tent city, Thousands of tents, sleeping, mess and latrine varieties. Then we were once again paired off and assigned. It finally happened Charlie and I were ordered aboard an English troop ship and nine days on the Mediterranean Sea.we spent a few days in a staging area, Charlie and I were destined for Italy, via British transport. We slept in hammocks suspended over wooden tables. We ate the lousiest possible food, drank the weakest tea and waited in line for a bottle of room temperature soda pop. Nine days again and we arrived in the Naples harbor, headed for a replacement depot.

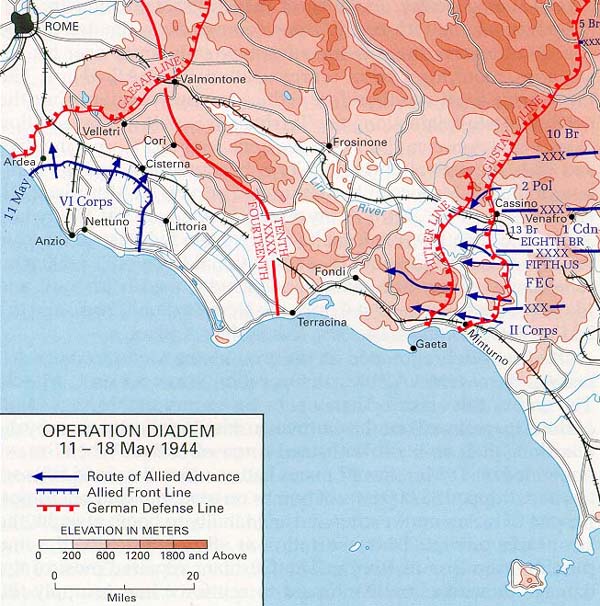

We were almost there. We were replacements, cannon fodder in the local terminology, headed for infantry units at the front. Our destination was secret, likewise our unit of assignment. But not for long because in three days we boarded LST's and sailed north to the Anzio Beachhead; we processed though a replacement center, a "repple depple" where we were assigned to our new units. I was assigned to the 45th division, welcomed to the Thunderbirds and hustled up front to the third battalion of the 157th regiment and eventually delivered to L Company. End of trip, end of acting corporal status, Welcome to the War!!

|

Right here we reach a benchmark in this old soldiers memory. Undoubtedly my two most meaningful military experiences are the Anzio Beachhead and the liberation of the Dachau death camp.

By the time we replacements arrived the beachhead routine was well established. We, the allies were sandwiched in between the mountains and the sea. The Germans were dug in on the high ground with all sorts of artillery and firepower was directed towards the seashore and us. The port of Anzio was as unsafe as any front line position. The area was barren, reclaimed swampland. Flat as a pancake, naked except for bushes and a few small trees, and crisscrossed by irrigation canals. Wild cattle, abandoned when the farmers were evacuated, roamed at will, often detonating German mines. Early on I learned that sheep dogs are among God's most intelligent animals. Since we avoided the roads during daylight hours to avoid German shelling, the dogs moved the cattle and sheep to graze near the roads in the daylight and far away up in the hills after dark. Surprisingly few cattle suffered from combat action but a large number succumbed to the soldiers' rifles. We like to think they had us surrounded so we shot and devoured them. Fresh meat at any price! The only major cover on the beachhead was the Pines, a rest area established in the imported pine groves along the sea on the Doris Duke estate. We were sure she wouldn't mind and she wasn't likely to be there during a war.

We camped there, we trained there, we relaxed there, we hid there and every night old Gerry's "Bed Check Charlie" flew over and tucked us in with a load of anti-personnel bombs. He always seemed to know just where we were despite light and noise discipline precautions.

Memories of the underground mansions of Anzio hit home for me. My buddy and I had a similarly constructed underground home away from home. We went up to the lines for a few days, usually rotated with counterparts in the 179th or the 180th, then came back to our ratholes. I remember using shell casings to let in air and light, and protecting the entrance from the possibility of a grenade or mortar shell falling into the entrance. I remember it rained and rained and rained and everything we owned was soaked. When the sun came out we stripped and scrubbed and shaved our heads and boiled everything we ever wore - the wool shrunk and had to be stretched and stretched. We made washing machines out of the big kitchen issue coffee cans - square jobs, held 25 pounds. We mixed hot water, GI soap, and gasoline and used the folded entrenching tool for an agitator. We boiled, scrubbed, washed - then four people would combine to stretch the OD's into some sort of shape and suitable size. What a life. I remember when we shoved off to leave that hell hole. We used to argue as to who's foxhole was best.

I am reminded that Americans will be

Americans under any and all circumstances. We brag about our women, our cars,

our jobs, our friends, our hobbies ---- you name it. And there we were on Anzio,

sandwiched between the mountains and the sea --- denied any real concealment

--- lacking cover, except for dirty canals --- no place to go without a major

battle. Moving mostly at night, using darkness to hide our resupply efforts.

And what did we do? We built underground mansions. I was a rifleman in "L"

Company, 157th Infantry. My buddy and I dug into that sandy, reclaimed, swamp-land

that was Mussolini's pride and joy for his collective farms, and did we dig!

Our home away from home was deep, deep, deep. It had to be so that we could

cut branches and stack them to get above the ground water level. I traded favors

and whatever to get my hands on every available blanket. Ordinarily I had one

in my full-field pack, but I had about 6 in my foxhole. Of course, they got

stinking damp and miserably chilly at night. We had a porthole type of skylight,

fashioned by digging a well-light tunnel to daylight, and inserting an ammo

case from the nearest artillery. We covered this skylight at night and burned

candles or lamps by burning gasoline in ration cans, using anything for a wick.

We kept rotating between front lines and the rear area, usually moving up and

back and trading with the same units, foxhole for foxhole. We offset the entrance

to prevent stray shrapnel or mortar fragments from intruding. We light-proofed

the burrows and we bragged about our accomplishments. Remember, I also remember

one time when we were up front, with only a few yards between us and the enemy,

on flat open terrain. We moved in at night, stayed hidden during the day. We

got tired of that routine so we got some flamethrowers and one night we crawled

out and spread napalm all along the front, as close to German lines as we dared.

Then we got back to safety and lobbed white phosphorous grenades into the napalm

after making a lot of noise and faking an attack. The enemy poured out to stop

us and ran into the wall of flames ---- from then on we could walk erect even

in daylight. That was typical of the guys I was privileged to serve with ----

they refused to cower and live in fear.

|

|

Mildred

Elizabeth Sisk

(aka Axis Sally) |

It was here also that we listened to Axis Sally, the Berlin Bitch as she broadcast her trashy music and stupid messages encouraging us to go home and kill the four f draft dodgers she alleged were dating our women.The Germans captured a truckload of our mail forwarded from Naples and turned it over to Axis Sally who used excerpts to taunt us. We used to get close to the armored units because they had better radios. I recall sitting in the sand among the pine trees of the Anzio Beachhead in spring 1944 and listening to the broadcasts. The pine forest was on the Doris Duke estate, the only major concealment on the beachhead.

Sally would play corny music and read bits and pieces from our letters. The Germans got several sacks, including those intended for our battalion. I think it was the Germans, but it could have been an inside job by some enterprising Neapolitan who got paid in lira or cigarettes by the Krauts. Anyway, Sally read a letter from my fiancée and then encouraged me to get angry, go absent without leave, hurry home and kill the 4F slacker that remained behind and had dated her. The man was a friend named Tom with a bad heart. He was 4F but not by his choice. Of course, Sally described it as a lover's tryst. It was supposed to be stressful and destroy our morale, but her personality and music was so corny, her message so rude, her style so unreal, that most of us got a good laugh.

We listened but it was so corny it was entertaining and if anything contributed to our morale.

Life on the beachhead was simple survival while occupying a fish bowl positions. We had only about a third of the necessary troops and logistical support. The port was too unsafe to permit major unloading. Gradually we built up firepower but it took four winter months of sand and rain and hail and misery. Every day we hid underground in elaborate foxholes, every night we sallied out on patrols and harassed the enemy forward positions. We went up front, about ten miles, switched placed with our sister regiments, stayed a few days and rotated back to the rear. We ate k rations, c rations and a few hot meals. We were limited to what we could carry on our person. I recall taking up pipe smoking there because cigarettes were in short supply.

I was assigned as a rifleman to the

third platoon to a squad commanded by someone called Corporal Touchhole Seymour.

Seymour was loud, crude, profane, wild and loveable. My basic training buddy

Charlie was assigned to the second platoon and on the very first night a concussion

grenade killed him, while on his first patrol. I lived to regret my promise

to protect Charlie and eventually I had not only to write his parents a letter

but I had to make a trip to his home after the war. I owed his aging parents

the details of his quick, painless death.

|

|

foot

power

drill |

We saw movies when in the rest area. Here we also got hot meals and had church services. I recall erecting a wooden cross on the hill above the beach and helping the Chaplain conduct Easter services. He baptized dozens in the sea. I got to play the field organ. Here too, I sent my sweetheart a corsage, which she received two month late. We shaved our heads to avoid lice and sand mites. We washed our woolen clothes is a soapy-gasoline mixture. We took cold water showers as often as we could. I received dental work .The dentist had a foot powered drill. Amazingly, that particular filling lasted over ten years.

On the Anzio Beachhead on April 9th of 1944, I was privileged to play the portable field organ while Chaplain Loy preached and Cpl. Thumpser sang. We were seated on our helmets on a hillside overlooking the sea. We walked the shores and were baptized or reconfirmed on the very spot where the Apostle Paul had converted the early gentiles. At sunrise, several hundred G.I.'s sang and prayed and shed a homesick tear. Eight months later many of the same men, plus new replacements, would gather at an improvised chapel in Neiderbron in Alsace. It would be Christmas Eve 1944; we sang the seasonal carols, played the traditional music. Not once but twice to accommodate the overflow crowd; all of us missing home and expressing it in song.

We skip ahead now to spring and May and the 23rd in 1944. It was breakout day on the beachhead. Artillery and air corps bombardments set the pace, tanks lead the way and off we went into the very jaws of the Boche guns. The casualties were legion and yours truly was among the earliest. I recall moving forward when artillery came down on us from all directions. I took a hit in the left shoulder. It was serious and required more than field medic attention. I was forced to turn back and to wade in the canal and try to find the aid station. I don't know when, where or how, but evidently shock set in and I passed out. Someone lifted me out of the canal. The litter bearers found me and I awakened in the hot, stuffy but safe ward on a hospital ship bound for Naples. I had passed through the battalion aid station and the evacuation hospital. It was hell on earth. The area was alive with the smell of burned flesh. Soldiers screamed from all sides. I was taken to the 300th General Hospital were over three thousand casualties awaited treatment.

|

|

Marlene

Dietrich

|

Oh how I learned to love the medical staff and the Red Cross people. It took over a month but I recovered. My outfit was somewhere on the outskirts or Rome, thousands of Americans were storming the Normandy beaches, and I was well on the way to recovery, thanks to the marvelous support and medical attention of the300th General Hospital in Naples, Italy. I was among three thousand patients crowded into the 1000 bed facility. I had recovered to the point that I was mobile. Everyone was expected to pitch and help. I opted to help the Red Cross. Under the direction of Miss Mary Breen Ratterman from Alabama, the 300th General Red Cross detachment was a life saving miracle in action. Ms Ratterman was one of God's special angels and she loved her soldiers. She assigned to escort a USO troop that was arriving to entertain the troops. Bright and early, about 7:30 a.m. one morning I stood at the main entrance and welcomed the troop. To my delight the headline was the one and only Marlene Dietrich! She arrived in a rush, she returned daily for an entire week, she remained and left in a rush. It was her style.

First order of business was a show,

presented to the patients who were able to gather in the huge cafeteria/dining

hall. Marlene sang, did magic tricks and told raunchy jokes. She was clad in

a translucent, shimmering blue gown, slit to reveal those million dollar legs;

speaking of nice legs, I was and remain a "leg man.". Before she turned

the show over to her supporting musicians and entertainers, she hiked up her

dress and paraded across the stage. Then she started tossing autographed blue

garters to the audience. There was pandemonium, bedlam. Wheel chairs collided;

crutches and canes became weapons as the men fought to capture a prize. The

authorities had to stop the show to keep from adding to the casualty list. Marlene

then began a relentless, seven day, dawn to dusk tour of the entire hospital.

She visited every room except the quarantine ward. She sang, she joked, she

gave autographs, she flirted; she ran from bed to bed and room to room. I struggled

to keep up with her. She never stopped. She lived on cigarettes, coffee and

martinis worked 16-hour days every day, and was a hell of a trooper.

|

At one time she met up with Rita Hayworth's kid brother. He was wounded and distraught because he couldn't get a message home to tell his family that he was recovering. La Dietrich marched into the hospital commander's office, commandeered a phone and put through a call from Naples to Hollywood. She was able to link mother and son, transoceanic.

|

She was middle aged, she was a mother, in fact she was a grandmother, but unlike any grandmother that I had ever met. She was kind, caring and fun to be with. She autographed a picture for me and even signed a cartoon-like drawing that my girlfriend then, later my wife of many years, had sent me. Unfortunately the cartoon disappeared from the letter I sent to Jane. I always suspected some dishonest censor. I even tried to trace it but to no avail.

Finally the week was up and Marlene and company moved on. It was a tearful good bye. Few entertainers matched the Blue Angel with her husky voice, her glamour, and her genuine dedication to the troops. When she finally left I had to go back to bed for two days to recover from the pace of trying to keep up with her.

You can be certain that I became and

remain an avid fan, loyal to memory of Marlene Dietrich-the lady who laughed

at Hitler, refused his command appearance order and poured body and soul into

the WW II effort.

There is a long after sequel to this story about my first combat wound. At the age on 77 I attended a reunion of Anzio Beachhead veterans and met the evacuation hospital nurse that removed the shrapnel from my back. She helped prepare me for the hospital ship trip to Naples. We had a joyful, tearful reunion. And we remain in touch via e-mail messages. Ramona will be one of the first recipients of my completed CD.

One Purple Heart, one patched up shoulder and thousands of memories later, I was judged fit to return to my unit and this I did. Once again I had to process through a reception center or a repple depple as we dubbed them. I rejoined my unit, the Third Battalion of the 157th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Infantry Division. We were near Salerno. The unit had fought out of the beachhead, made it to the wheat fields outside of Rome, and then moved south to train for the invasion of Southern France. During training breaks I got to the Verdi Opera House in Salerno and saw an abbreviated version of Aida. Also toured the ruins of Pompeii. I tagged along with a group of Limey sailors and enjoyed their company and comments more than the scenery.

I do not believe I can track my years

without frequent and wonderful musical recollections.

In random order and subject to memory lapses I can recall the early songs my

mother sang for me. I remember also the early tunes we sang in Sunday school,

and the large part music played in Edith Hudson Hazlet's fourth grade where

she blended song and facts to shape our lives. Then there was the high school

glee club, the senior chorus, the operettas; the inspiring lessons learned from

Arla Wallace.

I must mention the sweet lady who came by weekly and shared a half hour of piano instruction. She set tone for many happy hours and miles and years. Music followed me into uniformed service and traveled the globe with me. I would like to mention the operas performed at the San Carlos or was it the Verdi opera house in Salerno, Italy? The cast lacked the usual lusty young tenors, missing because of the war. Older men and women filled in and performed as only Italians can.

I can't leave this area without a comment on the cornfields and the beans and the people. We were in a rural area. The people were simple, God fearing, mostly children and women and old men. The male population was off to war. Italy had surrendered and then declared war on Germany and was officially a co-belligerent. We were in pup tents, encamped on rich black lava type soil. Here they grew long green beans, flat and tasteless but nourishing. Our quartermaster bought these by the tons and fed them to us at least twice daily. We got so that we simply carried our mess kits over to the garbage pits were local kids waited with their gallon cans. They claimed every scrap we would have thrown away. We were also the local source for candy and treats, which we shared gladly. I met little Roberto, a five or six year old that came to camp to steal cigarettes from our tents. He had been shot in the foot and limped but he was quick and agile despite the handicap. I decided to put a stop to his stealing. Using sign language and candy as a bribe, I engaged him to guard my tent and I paid him daily with treats and lire and friendship. Roberto and the whole local population were there when our convoy pulled out headed for the ships that would take us to southern France.

|

|

M2

Flame thrower

|

I recall very little about the brief trip except the wonderful summer weather and the opportunity to swim daily in the warm waters. We had long briefings and daily drills and we worked forever on equipment maintenance. I was supposed to lead a rifle squad but just before the invasion the flamethrower operator attached to us, broke his foot. He stayed on the ship and I carried the 79-pound flamethrower ashore. That was an experience. We were in small landing craft that were supposed to run right up on the beach, but we got stuck on an off shore a sand bar and we had to go over the side and wade. It took two buddies pulling me, to get enough traction to make headway in the sand. That invasion, at that particular part of the beaches of St. Maxim was a cakewalk. German pillboxes were empty or quickly abandoned and after the final naval barrage we literally walked ashore. Our single casualty in our company that day was one man killed by the Bangalore torpedo he was trying to use to blow holes in the barbed wire.

|

|

M_51

Gas Mask

|

The local citizens met us. We received a royal welcome from the mayor and all of the locals. I finally got a chance to try out my high school French. It worked but only when the French people spoke slowly. When they talked rapidly and used their local dialect, I was lost. For the rest of the war I would be struggling to communicate and become rather fluent in the language. Here, I recall we all emptied out our gas mask carriers and filled them with candy and cigarettes and chewing gum. Perfectly good gas masks were strewn everywhere and the frugal French gathered them up.

Thus we began a walking and riding trip due north from southern France. We rode for hours in what we called six byes, huge trucks. We took prisoners by the hundreds. We encountered pockets of fleeing Germans. The air corps gave us close in support by day and we lit haystacks and used the flames to light the roads, which we shelled constantly, night and day. Everywhere we went we were welcomed liked heroes. We were given fresh farm produce and when possible, we got local folks to cook us eggs and chicken and we traded canned and preserved rations in exchange.

Two references come to mind, first the Bible bit about casting your bread upon the waters, and second the Army doctrine on early escape attempts when captured. I assure you both doctrines are sound and I speak from personal experience. Official records do not confirm my brief capture by the Germans because it happened that I was captured, transported, strafed, escaped and back with my unit all in the course of a few hours.

It was 1944 and we had chased the Boche up the Rhone Valley and were headed towards the Vosges Mountains. German resistance was weak and scattered, with a few exceptions when they tried to stop and defend. The lines were fluid and indistinct. Dumb me, I wandered away from my squad only a few yards and came upon a farmhouse. I scouted out the place, went cautiously inside alone and without backup. Sure enough there were two German soldiers inside. They were armed and I was taken prisoner and marched away to join three or four more hapless yanks. We were loaded into a canvass-covered truck, watched over by a very young and nervous guard, and transported away, on our way to some prisoner enclosure. The only thing they did was quiz us for identification and organization and they did check our dogtags to see if we might be Jewish.

|

We hadn't gone more than a mile or two when I noticed that our young guard was nursing a sore left arm and showing signs of bleeding. I don't think the lad was more than 16, if that. I convinced him to let me see his arm. He had a flesh wound that needed attention, which I offered. I broke all the rules when I emptied my own first aid pouch and dosed him with sulfa powder and cleaned and bound the wound and made a sling with some canvass and adhesive tape. My guard was suspicious but needed the help. My fellow prisoners were critical and said I was crazy; let him bleed. Minutes later we were strafed by two American aircraft. Our truck was hit but we were ok. But we stopped and leaped out and I for one found a culvert and dived into it.

Others followed, including the guard. When the planes were gone, they rounded us up but my guard pushed me in the other direction and pointed and said "snell, snell" which I took to mean quick, go! And I did. I ran and hid and he must not have reported my actions because the trucks left without me. I hid out for the rest of the daylight and just after dark along the road comes a convoy, trucks from my own battalion and I made quick contact and got back to my company. I had been missed but not reported missing in action. I told the company commander what happened and got a lecture about my carelessness. After food and water and some rest, I went in search of new supplies for my first aid kit. Our field medic was a Quaker from eastern Pennsylvania and he alone seemed to appreciate the correlation of my helping the guard and then the guard's aiding my escape. No official record was made because theater policy was to reassign ex prisoners of war. I didn't want to leave my buddies while there was still work to be done.

In a French home in the town of Rambervillers, four of us visited and music was our common language. A daughter of the house played the piano and the song we all knew was The Isle of Capri. We didn't know it then but that chance meeting and the friendships forged would regenerate when one of our men, now a middle aged widower, would return and court and marry the pianist. She was a gifted musician with a lovely soprano voice. We relived our memories in reunions over the years in Colorado, Missouri, Texas, Georgia and Virginia.But I get ahead of myself I forget to comment on the Lutheran Church in Alsace and the Sunday we soldiers joined with the locals to sing Eine Festeburg, A Mighty Fortress is Our God!

I remember Epinal and Rambervillers and Moyen and suddenly it was fall and we were in the Vosges Mountains, which were to be our winter nemesis. Cold, snow, ice and determined German resistance.Our ranks were thin; we stopped several times for replacements. We retrained them, time permitting. I had been with L Company, later with K Company and now I was transferred to the operations section of our battalion where I remained for the rest of the war.

I used my French to help quarter our

troops when we were fortunate to stay in a village. I remember two weeks in

Rambervillers where I was quartered in the bakery operated by Momma Remy and

her nephew Andre. I supplied the flour and ingredients and she baked up a storm

of wonderful French bread and rolls and cakes. Momma Remy was a World War I

widow and she mothered me and all of the soldiers.

I recall also staying in Moyen with the local butcher who was also the mayor.

Papa Kim and his wife and niece and daughter lived in this small village. As

usual the young men were gone to war. Here I met and fed little Marcial and

his sister. They had never tasted chocolate. They lived mainly on local produce,

chicken and rabbit. Imports were non-existent.

We moved into Alsace. Christmas was approaching and we dreamed of going home. We sang I'll be home for Christmas but in our hearts we knew there was a long way to go before we defeated the Nazis. Christmas eve was spent in the Yodquellenoff Hotel in Niederbronn Les Bains or Bad Niederbronn depending upon your French or German preference. Everything in Alsace was bilingual. Here our three chaplains combined to conduct a wonderful Christmas Eve service with song and poem and prayer and lights and the holiday message. We converted the hotel porch into a church of sorts. Attendance was near one hundred percent. We had plenty of talent. Not a dry eye in the place. We started at eleven p.m. and finished at midnight when a convoy from the nearby engineer outfits arrived and we did it all over again. The cooks provided coffee and sheet cake.

|

|

click

map for larger version

|

Back to the war and the winter and the Battle of the Bulge. We were strung too thin when Hitler played his final attempt to stall our progress. We faced armor and artillery and were forced to give up over twenty kilometers in a single day. As the Germans reclaimed the towns they killed and terrorized the local people who had befriended us. In one case they hanged a Lutheran pastor because he let us hold services in his church.

It was here we saw our first jets, tiny, swift specks racing across the skies. We didn't know what they were at first. We suffered many losses as we bore the brunt of the southern end of the bulge.

Ike himself toured the front and visited our troops. Sometime in January 1945 and somewhere inside Germany, right after the worst of the fighting that we now know was the southern sector of Hitler's last hurrah, the Battle of the Bulge. I recall the ice and snow and the miserable cold.

I was serving as the operations non-com in our battalion headquarters. Our CP

and living quarters or the time, was a vacant farmhouse. The boss, our battalion

commander had just motored, jeeped off to regimental headquarters where he was

to meet some big brass. Better he go there than have the brass visit us here.

|

I recall I was clad in my long johns, had my feet near a roaring fire and was enjoying the shelter when the night silence was broken by the noise of a vehicle and the unexpected shout of a sentry's challenge. We thought the colonel had returned but when the door burst open we were amazed to be looking at whom else but IKE himself. He was cold, wet, shivering and definitely not smiling. In his jeep, with only a driver and an aide, he was lost.

Somewhere as they toured the front, this most important man in the entire theater of operations, had become separated from his escort convoy. They were awaiting him at the regimental CP and he was here with us. After we snapped to attention and reported and stammered the news that the CO was at regiment; Ike grabbed a chair and said you can get on the horn and tell them where I am; but he said we were not to do it just yet. He wanted to thaw out-he was cold-he wanted to dry out and we offered the fireside. I had spanking new long johns just obtained from the portable laundry unit that had visited us…

Ike donned those while we dried his OD's and he got on the outside of a sandwich and hot coffee laced with schnapps. He asked questions, checked out our situation map, encouraged us and predicted that Easter would find us all homeward bound.

An hour or so later, a now dry, warm

and smiling CG made ready to go to our regimental CP. This time we sent an adequate

escort. We never heard what happened to his original traveling companions but

we all cherished this intimate encounter. Chalk one up for this small town lad

who can forever after boast that General Eisenhower departed, wearing my long

johns.

We had logistical foul ups galore and often were short of mortar and machine gun ammunition. We were forced to hold up and wait for supplies, stop and go, march and fight, from village to village. Passed the Maginot Line and finally crossed into Germany via the Siegfried Line. We were confident that now would be the final blow. We were in Germany and everyday we heard rumors of Hitler's having to surrender. We crossed the Rhine and headed for Bavaria. Resistance varied from town to town. Aschaffensburg was brutal. Here we captured a Hitler youth camp where they were training young men to become SS troopers. They called it Wasserkruppe and I wonder what ever happened to the several hundred brainwashed kids. They were blonde, blue eyed and Ready to die for der Fuehrer. Despite the growing rumors the war didn't end when we reached Nuremberg. Our next goal was Munich and we were certain that the Third Reich would collapse right where it began.

last revision