LT Robert M. Barnhart |

|

45th Infantry Division, the Thunderbirds

How 45th Division Got Its Insignia.

I was curious as to why the 45th Division members used shoulder patches with Thunderbirds on them to identify themselves and I quickly learned why. The 45th Division was, at one time, the National Guard unit of both Arizona and Oklahoma. As populations grew, the 45th Division became the Oklahoma National Guard under control of the Oklahoma governor. A majority of the division's guardsmen were of Indian descent and, for this reason, they adopted an Indian sign, the swastika, as their emblem. When Hitler began the use of the swastika to identify his Nazi organization, the 45th Infantry Division immediately changed its emblem to another Indian sign, the Thunderbird. I found it very interesting that there are two Indian swastikas, one of which is the reverse (mirror) of the other. One is the good luck sign and the other is bad luck. The 45th Division had used the good luck sign but Hitler, without knowing anything about Indian lore, chose the bad luck sign of the Indians. Army Alphabet - Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog, etc.

|

|

"Me future is sealed, Willie. I'm gonna be a perfessor on types o' European soil." Printed

with permision from the Stars and Stripes, |

I

was greatly surprised at the appearance of our soldiers when we left Epinal. They

looked much more like Willie and Joe than like soldiers I had been on maneuvers

with in the United States. The veterans were permitted to carry a weapon of their

choice (one that they felt most comfortable with) and many of the men carried

spades, cross saws, and axes instead of the conventional G.I. entrenching tools.

I

was also surprised to see how they "dug in" and how quickly they dug

in at each stop. Instead of looking like fox holes their dugouts were more like

dens. The minute we stopped marching, the men went into action. Men with shovels

began digging "pits" about 7 to 8 feet long, four feet wide, and 3 feet

deep. The men with cross saws quickly teamed up with other men and began cutting

down small trees, 4 to 5 inches in diameter, which were cut into 5 feet lengths.

The small logs were then spread across the pits, covering the holes except for

a 2 or 3 foot opening at one end. The shovelers spread the loose dirt from the

pit over the top of the logs forming a small mound over which they spread shelter

halves if it was raining. These "foxholes" were unlike anything I had

seen before. They were always large enough for two or three men to sleep in; no

soldier was ever left alone in the night.

After we finished our digging there was nothing to do but sit and wait. I found out there would be a lot of sitting and waiting and I came to like the waiting part; it was far more desirable than fighting. My platoon sergeant had a hole dug for the platoon medic and me so I spent 10 or 15 minutes with the medic to get better acquainted with him. My feet felt hot and dirty after our long march so I decided to walk down the hill to the creek and wash my feet. The cool water felt good. After soaking my feet for awhile, I dried them and put on a fresh pair of socks. I tied the laces on my combat boots and, just as I was preparing to buckle the upper part of the boots, I heard a strange noise I had never heard before. No one had to tell me what it was; I knew it was an artillery round coming in our direction.

I jumped up and ran as fast as I could toward my dugout. The fluttering sound got louder and louder as I ran. I was almost to my dugout when it sounded like the artillery round was directly over me. I fell face down as the artillery round hit in a tree above me and exploded. I had fallen with my arms extended in front of me. After the explosion I saw a wisp of smoke coming from the ground under my right wrist and I heard several men screaming. I looked at my right arm and there was an approximate 2 1/2 inch slit in the sleeve of my field jacket, paralleling my wrist. If the fragment of shrapnel had been turned 90 degrees, it would have severed my right hand from my wrist.

I could hear the men in the Weapons Platoon hollering "Frenchie's been hit." I then heard Frenchie crying for his Mother as he died. I found out later that it was not unusual for men to cry for their Mothers when they were seriously wounded. These men were, in reality, boys; most of them were 18 or 19 years old.

I was within 16 or 18 feet of my dugout when I hit the dirt. As I got up and walked toward the dugout I could hear a commotion inside. A piece of shrapnel had gone through the dugout entrance and wounded my Medic in his leg. I never knew how badly he was wounded because I never saw him again after he was carried off.

The reason our men prepared the dugouts as they did was because when artillery is fired into a wooded area, the projectile almost always hits a tree limb and detonates. The small logs and dirt on top of the dugout almost always protected the soldier from bursts of shrapnel. The wound my Medic received was very unusual.

The artillery round that hit our company area must have been an errant round resulting from a miscalculation by a German artilleryman. The Germans used interdictory fire off and on all afternoon to prevent the use of the road below us; however, there were no other rounds that came close to our company area.

I was very fortunate to be assigned to the 45th Infantry Division. Personnel in this group were among the very first to go into combat in the European Theatre. They had participated in the invasions of Northern Africa, Salerno, and two in Italy, including Anzio. I talked to men from other divisions after the war and none indicated their organizations were anywhere close to being as well organized as the 45th.

Almost every night immediately after the sun went down our two company jeeps (with trailers) would bring bedrolls and hot food to us. They would stop several hundred yards behind our position and each platoon would send several men to carry up the food and bedding. There were always two large hot food containers for each platoon, one of which would be filled with meat and gravy and the other one would be filled with some hot vegetable, usually potatoes. There was always a bedroll for each man that consisted of two wool army blankets tied together with a rope. In addition, each platoon received a box containing cigarettes, razor blades, toothbrushes and toothpaste, etc. There was always enough of the necessities to replace items that had been lost or used up.

Each morning we would get up before sun-up and tie up our bedrolls. We would send several men back to the point they rendezvoused with the jeeps the night before. They would carry back the empty food containers and bedrolls, exchanging them for fresh containers of breakfast-type foods and boxes of K Rations (our lunch).

|

I

doubt that any of our jeep drivers received medals for their work, but they deserved

them. They would find us on the darkest nights, sometimes in blinding rain or

in snowy blizzards, and they would follow trails that would be dangerous for a

mountain goat.

Our

little dugouts afforded much protection from the elements and incoming enemy fire,

but they were uncomfortable to sleep in until you got used to them. I don't know

how other men slept, but I always slept back to back with my partner, cradling

my rifle in my arms. I found that the hardest thing about sleeping on one's side

was to find a comfortable place for your hip. There were almost always rocks or

tree roots in the way. I would maneuver around until I finally found some kind

of a depression for my hip. I would usually freeze (remain stationary) in that

position for the entire night. Usually we were so tired by nighttime that we could

sleep almost any place.

|

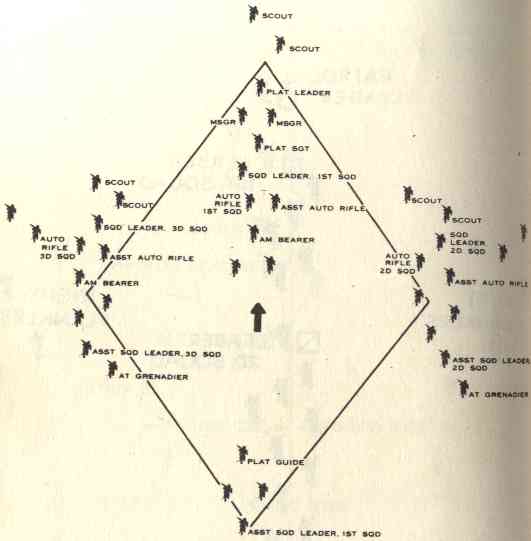

During the second day out I was asked to do several things that gave the company officers some idea of my combat worthiness. I was never told that I was being tested, but it was obvious to me that I was. Shortly after breakfast our company commander assembled the platoon leaders and briefed us on plans for the day. We then went back to our platoons and prepared to move out. After we had marched for a couple of hours, our forward movement brought us into a more level and barren area than was characteristic of the Vosges Mountains. My company commander, a young man named John Rahill, came to me and asked me to lead the company for the next two or three miles. He gave me a map and showed me the route he wanted me to follow. There were no roads; he pencilled the route along grid lines and significant landmarks. He then told me to take the point of a diamond patrol and move out. He said that the remainder of the company would follow my patrol, keeping about 200 yards behind me.

For what seemed an eternity I led the diamond patrol with my rifle strapped across my back; I had my compass in one hand and the map in the other. Should the enemy be ahead, I knew that I would be the first target. I was more concerned about snipers than a German infantry group because these men were deadly up to 1,000 yards. They had special rifles with glass sights. They always worked in pairs so one could certify the other's kills. After the war I learned that some of these snipers were credited with more than 600 kills. About noon I was called back and told to rejoin my platoon.

Shortly before dark we reached our assigned area for the night. Directly ahead of us the terrain was rougher than usual which made it difficult to set up an F.P.L. (Final Protective Line) for the night. Before darkness set in, our machine guns were set up along lines that would be most effective. It was desirable to block the guns at an elevation that would keep its bullets not more than 30 to 40 inches off of the ground for the greatest distance possible. The guns were arranged so that their lines of fire crisscrossed each other. Mortars were zeroed in to cover the dead spots not covered by machine gun fire. A small canyon started about 300 yards in front of us that was too wide to be closed with mortar fire.

After we dug in and had our supper, Rahill (our C.O.) told me they planned to zero in the canyon ahead of us with artillery fire. He told me to take one of the company radios and move forward to a position where I could direct artillery fire into the canyon. He told me to request lateral corrections on a line perpendicular to my front, and distance corrections in segments of 100 yards or more.

After I got into position, I requested that the first round be fired. It was really spooky sitting out there alone in the dark, wondering how the artillery had zeroed in their cannon for the first round. Then I heard the sound I was to become all too familiar with. The artillery shell fluttered overhead and landed in the canyon ahead of me. It was too far out so I requested that the next round be brought in closer. I then wondered if they might bring it in too close. After all, I was sitting on open ground at the edge of the canyon with absolutely no protection. After several corrections, the voice on the radio told me to return to the company C.P. I often wondered if there was an artillery F.O. (Forward Observer) who was close by, waiting to intercede if my requested corrections would have endangered anyone.

On the morning of the third day out I had a long discussion with my platoon sergeant, Lew Eaves. I asked him if he would continue running the platoon for a few more days. I told him I wanted to learn as much as I could before we became involved in a big fight. I told him I didn't want to do something stupid that could cost the lives of some of my men and that I would appreciate any and all of the help he could give me.

Our platoon had been given the mission to sweep a wooded area and, in so doing, we ran into a group of Germans. The firefight only lasted a few minutes before the Germans flipped off their helmets. I didn't know until that time that when a German surrendered, he dropped his helmet to the ground.

While we were at Epinal some of the men in my platoon had told me that Wilson was one of the best B.A.R. men in the Army. So, when the fight started, I purposely watched Wilson. What he did was something that made a lot of sense, but something we had not been taught in either basic training or O.C.S. The Browning rifle's clip held twenty rounds and it could be fired as an automatic or a semiautomatic rifle. It was difficult to handle as an automatic weapon because the muzzle would raise several degrees as each round was fired. Wilson had learned (or been taught) to turn this disadvantage into an advantage. Instead of firing the rifle from his shoulder, he turned it sideways and fired it from his hip. He would point his B.A.R. toward the right flank of the enemy and then fire a burst of twenty rounds, spraying bullets at ground level, traversing from left to right a sector of 30 or 40 degrees. Once he exhausted a clip he would shove in another and repeat the process.

When the Germans stood up, dropping their helmets, I heard Lew Eaves yell "Cease firing." They came forward and my men surrounded them, stripping them of jewelry and money. There were l4 prisoners in all, almost as many men as were in my platoon. One German who spoke perfect English had a shattered arm with a bone protruding through his wound. He was very bitter; he said they had planned to surrender before we opened fire on them. There was nothing I could say to him. I really didn't know whether they or we had fired first but I did know that he would be returned to one of our hospitals where he would receive the best of care and that we would continue pushing forward, never knowing what the next day (hour or minute) might hold for us.

I looked around for Lew Eaves but he was nowhere to be found. I asked one of the squad leaders if he knew what had happened to Lew and he told me that in the firefight, Lew had been hit. Our platoon Medic had helped Lew make it back to our company C.P. I never again saw Lew or heard anything about him.

|

One of our prisoners' weapons was a P-38 which was in mint condition. I took this weapon for myself and I prize it more highly than any other trophy I received during the war. The P-38 is a 9 mm. handgun which was mass-produced by the Germans and used as a replacement for the Luger.

Lew Eaves was the last of the original Indians in Company B. We had a replacement from California who was an Apache. Because of his small stature, everyone called him Little Chief. He had eyes that seemed to look right through you and he never talked unless he wanted something or he was mad. After we rounded up our prisoners, Little Chief asked me if he could take them back to our Company C. P. One of the men in my platoon spoke under his breath saying, "Don't let him do it unless you want them killed." I appointed another person to do the job. I later found out that when Prisoners were given to Little Chief he would take them part way to the rear, line them up and kill them all with his B.A.R. He was a peculiar person but he was not hard to handle unless he was drunk. If he got some drink with alcohol in it, he went crazy.

For some crazy reason I had the desire to shout, "Powder River, let 'er buck" when we were in a firefight. One of the fictional western heroes in my Dad's Argosy stories always did this but I knew better than to do it. It was best not to do anything that might draw the attention of the enemy. All soldiers, both German and American, were taught to kill officers and non-commissioned officers first. For this reason all American soldiers, officers and enlisted men, wore the same uniform in the field. Officers did not wear their insignia of rank on their field jackets. We did wear this insignia on the collars of our shirts, but we kept it covered with our field jackets as much as possible.

When we crawled into our little dugouts at night I usually went right to sleep because I was usually tired. Mental stress in combination with physical stress can really wear a person down. Although I dozed off about the time I laid down, I woke up just as easily. My nerves were so frayed that the slightest sound would awaken me. This problem of being aroused by unusual sounds in the night continued for many years after the war was over.

I was afraid that some German patrol might overrun our position under the cover of darkness. One of my runners, Ted Leiken, had a terrifying experience in Sicily. There they had nothing to cover their holes with. In the middle of the night a German patrol walked right into their company area without being detected. One German walked up to the hole Ted was sleeping in and as he stood there, one of our men spotted the German and shot him through the head. Ted was sleeping soundly when the dead German fell right on top of him.

When darkness set in at night, the darker it was the better I liked it. When it was so dark that I could not see my hand in front of my face I would sleep like a baby. I knew there was no chance of German patrols entering into our area.

Fortunately I was sent out only once to lead only one night patrol. It's really spooky to be in front of your line and know you have men behind you with their fingers on triggers and men in front of you with their fingers on triggers.

Each morning new signs and countersigns were given to us. When one of our patrols returned to our line at night it was challenged by a rifleman who requested the sign of the day. If you didn't know it, he was supposed to start shooting. After you gave him the sign, you asked him for the countersign and if he didn't know it, you were supposed to start shooting.

The

night I was sent out with a patrol I was told to move about a mile in front of

our lines to try to determine if there was any enemy activity. It was a beautiful

night with the moon shining brightly overhead. After we had moved forward about

2/3 of a mile, we heard a pounding sound. We continued toward the sound but while

approaching its source we moved beyond the timberline into an open field. We could

make out a large shed with very bright lights inside. When we moved up to within

100 yard of the shed we could hear Germans talking to each other and it appeared

they were working on some type of armored vehicle. We did not see any guards around

the building. However, I expected to see flares go up all around us and I wondered

if my men remembered what to do if a flare went up (you were supposed to close

your eyes and remain motionless). We returned through our lines and I advised

our company commander what we had seen and heard.

|

Smoking was made easy in the army, particularly if you were out of the states. In Alaska and the Aleutian Islands premier cigarettes (such as Camels and Lucky Strikes) sold for 5 cents a pack and the cheaper brands (such as Wings and Larks) sold for 4 cents. In Europe, cigarettes were free.

I will never regret becoming addicted to cigarettes while in the service. In times of great stress when there were periods during which nothing could be done except wait and pray, the tranquilizing effect of cigarettes was a big help for me. Smoking also gave me something to do with my hands. I can remember getting rid of a pack of cigarettes in less than an hour during an artillery barrage. I would take out one cigarette, light it, take three or four puffs, then I would throw it away. I would repeat this process every two, three, or four minutes until the barrage stopped.

Once every four, five, or six weeks, depending on combat situations, we were pulled out of the line and sent to the rear for baths. We marched back into an area where we boarded trucks to go to our bathing area. They provided us with a large truck that had a large portable bath and a second truck that had piles of O.D. woolen clothing, socks, and underwear. After bathing we exchanged our dirty clothes for clean ones. It was difficult to tell what size shirts and trousers you needed because the only method they had for cleaning the woolen was G.I. soap and boiling water. You know what boiling water does to wool clothes. So, we tried on the clean clothing to see if it fit. We found it was better to get clothes a little on the large size than to get them too small.

|

I got the surprise of my life when I saw some of the men in our company clean shaven for the first time. I particularly remember the platoon sergeant of the weapons platoon. He was a Latin type, swarthy skin and big brown eyes. I thought he was a handsome youngster until he shaved off his beard. He had no chin. He looked like Andy Gump.

|

Each K-Ration we received had a small tin of soluble coffee in it. However, one needed hot water to "make" palatable coffee. The small Coleman stoves were great for making coffee so we tried to keep two stoves in each platoon. There was one problem with these stoves; they were heavy. Each stove, including its metal carrying case, weighed four or five pounds. When we would get into a fire fight, my men would throw their stoves away. A few pounds made a big difference when you had to move quickly from one place of concealment to another. Some men would throw away every thing they had except for their weapon and ammunition.

When we "lost" some of our stoves I would ask our supply sergeant for replacements. After asking for replacements several times, the supply sergeant became nasty; he didn't understand why my men couldn't hang on to their stoves. I told him "Opal (his name was Opal Jones), if you think we are being unreasonable why don't you spend a day up front with me and my men?" I told him I was sure I could make arrangements with our company commander for him to spend a day or two with us. After that, he accepted my requisitions for stoves and other materials without question. He grumbled a little but he always gave us what we asked for.

I always carried a small pair of scissors and a pair of pliers with me. With these tools and my pocket knife I made various and assorted gadgets from time. One day I got a bright idea that a person might be able to make a light-weight stove out of the materials used to pack C-Rations and K-Rations. I made a frame from a tin can that would hold two round coffee containers, one directly above the other. I removed the lids from both containers and put a small amount of gasoline in each. I made a small slit in the lid of the bottom container into which I inserted a small piece of cloth. I made numerous small holes in the lid of the top container. I put both lids on their containers and prepared to complete my experiment. I thought that when I lighted the wick in the bottom container it would warm up the top container forcing gasoline vapors through the small holes I had made in its lid.

I was sitting in my little dugout, three or four feet from the entrance. I lit the wick in the bottom container and then held a match over the top container. The vapors from the top container ignited, making a beautiful flame. I thought I had stumbled onto something good but as I watched, the flame from the top container shot up higher and higher until it looked more like a flame thrower than a stove. I quickly kicked the "stove" toward the hole that was the entrance to my abode. As I did this the gasoline spilled from the containers and burned up in one big flash.

Unfortunately my platoon sergeant, Dennis Mitchell, had something he wanted to tell me at that time. He stuck his head in the hole at the moment the gasoline fire flashed. He wasn't burned badly but he did lose most of his eyelashes and eyebrows. Since I was an officer he didn't dare say anything, however, had I been an enlisted man I am sure he would have chewed me out.

Since each of us is different and each of us may perceive the same experience differently, I suppose the psychological effects of combat were different for each of us. I decided early on that I didn't want to be too close to anyone in my platoon, not that I didn't like them, but because of the effect it would have on me when one of them was killed. You never knew when you might have to dig in with the crumpled body of one of your men lying in full sight, a few yards away. When this happened, it was difficult to sleep at times, however, you learned to block things like this out of your mind. You didn't try to think of something else: you learned to block everything out of your mind. This, I suppose, is some form of self-hypnosis.

It was hard for me to make a complete emotional disconnect from my men due to the fact that I had to censor each letter they wrote. In reading their letters you learned a lot about them that you really didn't want to know. Most letters were written to a mother, wife, or sweetheart and most expressed feelings of hope or nostalgia, or both. I felt like crying when I read some of the letters but I didn't. This wasn't a manly thing to do so I saved all of my tears until many years after I came home.

Some men went completely berserk while in combat but this usually happened shortly after or during their first actual combat experience. Some went so far as to shoot themselves. Since these problems usually manifested themselves shortly after exposure to combat, most men with these problems were the rookies. However, sometimes a veteran would reach the boiling point after holding out for a long period of time. I believe that each of us had a limit but that we were able to extend this limit day by day, and month by month, by making ourselves believe that we were merely spectators and not participants in what was going on around us. I can't explain it but I believe the mind, like the body, has ways of protecting itself and healing its wounds. Sometimes the healing consists of pushing some things so far back into the mind that they can not be recalled without psychological help.

|

Artillery units had Piper Cubs (L-5's) that were sometimes used by forward observers (F O's) to spot the enemy and to direct fire on enemy positions. There were usually two men in an L-5, the pilot and an F O. One time when I was behind the lines an artillery F O landed in a nearby field. I walked over to the plane and visited with the pilot. He asked me if I would like to take a ride with him and I said, "Yes."

I was tense most of the time in the airplane. These planes have no protection and they fly at relatively low altitudes, low enough that they can be downed with a bullet from a rifleman. When we landed I had a new respect for these pilots and F O's. Theirs was one of the few jobs that I would not have traded for mine.

Once a month each officer received a liquor ration. The package usually consisted of one bottle each of bourbon, blended whiskey (usually Four Roses), Scotch, Cognac, and Vermouth. Since the enlisted men received no liquor, I usually shared mine with the men in my platoon.

The liquor ration I received the first of November I put in my bedroom. Each officer had a bedroom that was carried with the company's kitchen. In my bedroll I carried my dress uniform, my P-38 and Luger, assorted personal items, and my liquor ration. I had always thought whatever I put in my bedroll would be safe.

The day before Thanksgiving, 1944, we were sent to a rest area for a few days or, at least, we thought it would be for a few days. When we were pulled off of the line for Thanksgiving, I told my men that we would have a treat, that we would share my liquor. When I went to the kitchen and opened my bedroll, the liquor was gone. I asked the cooks who had taken the liquor and, of course, none of them knew anything about it. There was nothing I could do other than tell my men that I was sorry. I did register a complaint with our Mess Sergeant, "Stew" Malone.

You may wonder why I left my P-38 with the kitchen. If an American soldier was captured with a German hand gun in his possession, he was usually executed immediately. The Germans shoved the barrel of the weapon into the American's mouth and pulled the trigger.

On Thanksgiving Eve we settled down for what we thought would be a few days of rest and relaxation. The camp we were assigned to had tents with folding cots for our entire company. There was also a large mess tent were we could sit down and eat, and a second large tent where movies could be shown.

After supper on Thanksgiving Eve most of us went to the movie tent. I don't remember what the movie was but I do remember that we saw a news reel with a short sports special. This special was very interesting to me because it showed part of a football game in which the University of Georgia was a participant. On one play Andy Dudish threw a pass to George Poschner which he took into the end zone for a touchdown. Dudish and Poschner were friends of mine who had been with me in Company D, 176th Infantry at Fort Benning.

We had only been in bed for a few minutes when we heard the cry "Pack up. We're moving out as soon as the trucks get here." Thirty minutes later we were on trucks, moving up toward the scene of action. Our rest period was short lived.

About 1:30 or 2:00 a.m. we arrived in a small French village where we debarked from our trucks. By that time it was raining and it was cold and miserable. We were told to take our men into a Catholic church where we would spend the remainder of the night.

The floor of the church sloped downward toward the altar in the front of the church. There were numerous holes in the roof of the church where the rain poured through and when the water hit the floor, it flowed to ward the front of the church making it difficult to find a place on the floor where one could sleep without being soaked. Most of us were soaking wet by 6:30 a.m. when we were called to eat our Thanksgiving Dinner.

About 6:30 a.m. on Thanksgiving morning we were awakened to a pleasant surprise. Our company cooks had worked most of the night preparing our turkey "dinner". The cooks set up a serving line in the back of the church and while this was taking place, the parishioners of the church filed in and moved to the front of the church. While we were being served our turkey and trimmings, the parish priest was conducting Mass. Can you imagine being served a turkey dinner at 7:00 a.m. in a cold, wet Catholic Church while Mass is in progress? Also, can you imagine eating your meal out of a small oval shaped pan (mess kit) about 3/4ths of an inch deep? The mashed potatoes and gravy, cranberry sauce, green beans, turkey, celery sticks and pumpkin pie ran together in one big mess. However, it was good. Every Thanksgiving I think of Thanksgiving, 1944, and I think of how much we have to be thankful for.

The last day of November I was relieved of my duties and sent to a rest center at Nancy, France for four days. This was to be the only pass I would receive while we were in combat.

The rest center was an old hotel that probably had been used by the Germans for the same purpose as ours. When I arrived at the hotel and started up the steps from the street I had a very pleasant surprise.

Coming down the steps as I was going up was Rolland Brinkman, my friend at Ft. Benning. He had already been at the center for two days so our time together was limited. We visited, had dinner together, and he told me what the rest center had to offer, which wasn't much. The hotel provided a room and meals; as far as entertainment was concerned, you were on your own.

We learned that Bud Brown's division was in the lines not more than 35 or 40 miles from us so we decided to pay him a visit. We got up early the next morning, commandeered a jeep, and took off looking for Bud. Bud and his wife, Betty, were two of Aretta's and my best friends at Fort Benning. It was an ironic "postman's holiday"; we had been sent back to Nancy to be temporarily freed from the pressures of combat and here we were back in the middle of a combat area.

We

located Bud and had a nice although relatively short visit with him. Bud's company

had lost most of it officers and he had been promoted to the position of company

commander. Although the combat situation in Bud's area was static while we were

there, he was very busy answering his field phone and receiving runners with messages.

He seemed to be nervous so Rolland and I bid him goodbye after a short visit.

I thought it was interesting that Bud, Rolland and I had been assigned to the

3rd, 36th, and 45th Infantry Divisions which comprised the infantry for the 7th

Army and were the oldest divisions, in terms of combat time, in the European theater.

These divisions landed in Northern Africa, made the beach head landings in Sicily

and Italy, and fought their way from Italy to Germany.

last revision